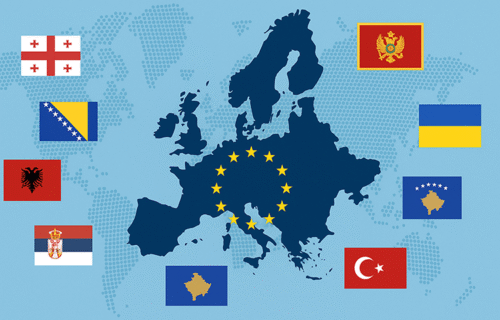

Europe is preparing for its most ambitious wave of expansion in decades, with ten nations from the Western Balkans to the Black Sea seeking to join the European Union. Their motivations are clear — stability, growth, and security within Europe’s political framework — but their progress remains uneven. Each country faces its own reform challenges, while the EU itself must confront internal doubts about its readiness to absorb new members.

Albania has emerged as one of the most determined reformers in the Western Balkans. Its government has launched a string of anti-corruption and digital governance measures, but the rule of law remains fragile. The EU continues to push for visible results in prosecuting high-level corruption and strengthening judicial independence. Despite progress, deep-rooted governance issues and uneven public trust in institutions still stand in the way of membership.

North Macedonia’s path has been blocked by political disputes that have overshadowed years of reforms. A constitutional amendment recognising the Bulgarian minority — a key precondition set by the EU — remains stalled in parliament. The deadlock has frustrated citizens who supported the country’s long-standing pro-European orientation and believe it has already delivered on most technical reforms.

Montenegro is widely seen as the closest to joining. It has opened nearly all negotiation chapters and provisionally closed several, but political instability and unfinished judicial reforms continue to slow its progress. Brussels sees Montenegro as a test case for whether the Western Balkans can deliver real change and whether the EU can keep enlargement momentum alive.

Serbia’s membership talks have lost momentum. Concerns over media freedom, judicial independence, and close ties with Russia have drawn criticism from Brussels. The EU insists that Serbia must align more closely with its foreign policy and normalise relations with Kosovo before meaningful progress can be made. Without these shifts, its accession track risks indefinite delay.

Bosnia and Herzegovina remains paralysed by internal divisions and an unwieldy power-sharing structure that makes nationwide reform difficult. Despite cooperation with the EU on border management and migration, real institutional reform remains elusive. Until the state functions more cohesively, the country’s European path will remain largely symbolic.

Moldova, on the other hand, has surprised observers with its rapid reform drive. Since being granted candidate status, it has launched judicial restructuring and anti-corruption measures while trying to reduce dependence on Russian energy. Yet its limited administrative capacity and exposure to geopolitical pressures pose ongoing risks. The EU has praised Moldova’s determination but warns that momentum must translate into measurable results.

Ukraine’s path to membership is exceptional — it is pursuing structural reform in the middle of a war. Even under extreme pressure, Kyiv has strengthened anti-corruption institutions and pursued regulatory alignment with EU standards. The challenge now is to sustain reform while defending the country militarily. EU officials link future funding and accession milestones to continued governance progress, knowing that Ukraine’s success will shape Europe’s credibility as a geopolitical actor.

Georgia’s accession hopes have dimmed. Once seen as a frontrunner, the country has drifted away from democratic norms, with its government accused of undermining media freedom and civil society. Brussels has urged Georgian leaders to return to the reform path laid out in their initial roadmap, warning that political backsliding could halt progress entirely.

Turkey’s membership process remains effectively frozen. The EU continues to cite major concerns about human rights, press freedom, and judicial independence. While cooperation on trade and migration persists, full membership is no longer viewed as a realistic prospect under current conditions.

Kosovo’s path is complicated by a lack of universal recognition. Five EU member states still do not formally recognise its independence, which makes the accession process legally and politically difficult. The EU continues to press for dialogue between Pristina and Belgrade, seeing reconciliation as essential for both countries’ European aspirations.

For Brussels, enlargement is as much a political question as a technical one. Every new member must be approved by all existing 27 states, leaving the process vulnerable to national vetoes and political bargaining. At the same time, the EU must ensure it can function effectively once new members join — a concern frequently raised by larger states wary of overextension.

The geopolitical context has made enlargement a renewed priority. Russia’s war in Ukraine and growing Chinese influence in the Balkans have transformed what was once a slow bureaucratic process into a strategic race for influence. Yet the balance remains delicate: candidate countries must prove genuine reform, and the EU must show that its promises are credible.

Europe’s future enlargement will test both sides. The candidates need to demonstrate that they can uphold European values in practice, not just on paper. The EU, for its part, must show that its door remains open in more than rhetoric. Whether this new wave of enlargement becomes another success story or another stalled process will depend on a single question — can Europe deliver on its own vision before momentum fades once again?