The evolution of Germany’s labour market over the past four decades reflects more than the familiar pattern of jobs shifting from factories to offices. A recent analysis by researchers affiliated with the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) and the Deutsche Bundesbank shows that much of the apparent loss of industrial employment has been offset by new types of work emerging within the service economy, often involving the same skills and occupations once found in manufacturing.

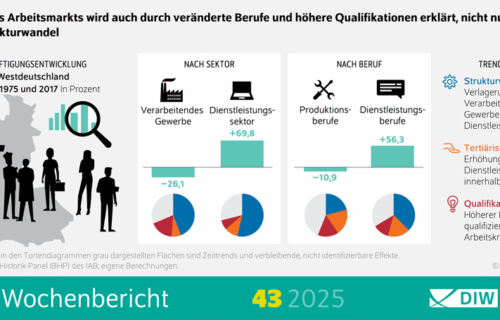

The study examines employment data for West Germany from the mid-1970s to 2017 and finds that the country’s industrial workforce has contracted sharply, yet many of those who might once have worked on production lines are now employed in service-sector companies that perform similar functions. The result, the researchers argue, is a quieter but deeper transformation — one in which the boundaries between industry and services have blurred.

Over the period, roughly half of all industrial job losses were effectively absorbed elsewhere in the economy. While production plants shed workers, logistics, maintenance, quality control and technical design roles multiplied across business services, retail and technology firms. The underlying tasks remain industrial in character but are now carried out in a different environment and often require higher qualifications.

This development also points to a growing divide between low- and high-skilled workers. As automation reshapes production and data management becomes central to business processes, demand for technical expertise, engineering knowledge and digital skills continues to rise. At the same time, opportunities for less qualified workers have narrowed, particularly in traditional manufacturing regions.

According to DIW economist Thilo Kroeger, the changes reveal how “structural” adjustment today takes place not only between sectors but inside occupations themselves. The same job title, he noted, may now involve entirely different tools, workflows and responsibilities compared to a generation ago.

For policymakers, the findings underline the importance of retraining and lifelong learning. Rather than focusing only on which sectors are shrinking or expanding, economic and education policy needs to anticipate how work content is changing across the board. Preparing workers to adapt to these shifts — especially those in routine or lower-skilled positions — will be key to ensuring that the next stage of Germany’s industrial evolution remains inclusive.

The research adds to a growing consensus that Germany’s economy is entering a new phase in which services and manufacturing are increasingly interwoven. The future of work, it suggests, will depend less on where people are employed and more on what they do — and how effectively they can evolve with their tasks.

Source: DIW Berlin