Employment across the European Union has reached its strongest level on record, and for the first time in more than a decade, the fastest growth is coming from the south. New Eurostat data show that regions in Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy are closing the long-standing gap with northern Europe, powered by tourism, public investment, and post-pandemic reforms that have drawn thousands back into the workforce.

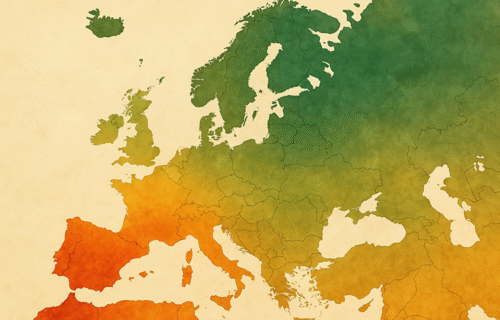

For people aged 20 to 64, the EU’s employment rate climbed to 75.8 percent in 2024, a historic high that brings the bloc within striking distance of its 78 percent target for 2030 under the European Pillar of Social Rights. Nearly half of Europe’s 243 statistical regions have already met or exceeded that threshold. Northern countries continue to dominate the rankings — the Åland Islands in Finland lead with an 86 percent employment rate, closely followed by Warsaw, Bratislava, and Budapest — but southern Europe is where momentum is now strongest.

In Greece, employment has rebounded dramatically since 2021. The recovery has been driven by tourism and hospitality, but also by targeted government measures such as higher minimum wages, lower payroll taxes, and investment in green and digital sectors. According to economists at Thrace University, more than half of new salaried positions created in recent years stemmed from service industries, particularly food, retail, and leisure. The effect has been visible in once-struggling islands and coastal towns where seasonal labour shortages have turned into hiring surges. “Tourism has reached its short-term ceiling,” one Greek analyst said, “but if regional investment and reskilling continue, these gains can become permanent.”

Similar recoveries are being recorded in parts of Spain and Portugal, where record visitor numbers and energy transition projects have boosted job creation. Italy’s labour map shows a more uneven picture: while the north remains near full employment, southern regions such as Calabria, Campania, and Sicily still rank among the EU’s weakest performers, with employment rates barely above 50 percent. Economists warn that much of the new work in southern Europe remains concentrated in lower-paid, short-term service roles, raising concerns about job quality and long-term stability.

Further north, Germany’s once-robust industrial hubs have started to contract. Manufacturing regions like Thuringia and Saxony have recorded modest employment declines as high energy costs and weaker exports strain an economy long reliant on global demand. Analysts say Germany’s export-driven model has reached a turning point, with productivity slowing and domestic consumption yet to fill the gap. Central Europe, meanwhile, continues to perform strongly. Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia maintain employment rates exceeding 85 percent, reflecting their diversified manufacturing and logistics sectors, although growth there has largely stabilised.

The contrasting trajectories highlight how Europe’s post-pandemic recovery has reshaped its labour map. The south is catching up, the centre is consolidating, and parts of the industrial north are treading water. The European Commission views the trend as proof that cohesion and recovery funds are beginning to deliver results where they were needed most. Billions in grants and loans from the Recovery and Resilience Facility have been channelled into renewable-energy projects, infrastructure, and skills training, all designed to raise employment and reduce regional inequality.

But behind the headline numbers lie more complex questions. Economists caution that the EU’s labour rebound could plateau in 2025 as tourism reaches capacity and government stimulus fades. Many of the fastest-growing sectors in the south depend heavily on seasonal or service work that offers limited security or career progression. Without continued investment in technology, education, and innovation, the risk is that these regions could stall again once the travel boom subsides.

Labour market experts also note that demographic change is emerging as a new challenge. Ageing populations in much of Europe are shrinking the working-age pool, particularly in rural and peripheral regions. That makes digitalisation, reskilling, and targeted immigration policies essential to sustain employment growth. The EU’s goal of having 60 percent of the workforce in training each year is therefore becoming central to its long-term competitiveness agenda.

Local stories reflect both the opportunity and fragility of the recovery. In Crete, hotel operators report hiring at levels unseen since 2008, while in Lisbon, a growing start-up scene has absorbed young graduates who once sought work abroad. Yet in Calabria, many of those who left during the pandemic have not returned, and employers struggle to fill vacancies outside tourism.

For now, the overall picture remains positive. Europe’s labour market is more balanced than at any time since the global financial crisis, with southern economies finally closing the gap that once defined the continent’s economic divide. But sustaining that progress will require transforming short-term service-sector gains into higher-quality, innovation-driven employment.

As one senior EU labour official remarked privately, “The success of Europe’s job recovery won’t be measured just by how many people are working — but by what kind of work they are doing.” The coming years will test whether the continent can translate record employment into durable prosperity, ensuring that the south’s comeback becomes a structural shift, not another temporary surge.

Sources & References: CIJ.World analysis based on Eurostat regional employment data (NUTS 2, 2021–2024), European Commission labour market communications, and verified academic commentary.